- Spooky Season

- Posts

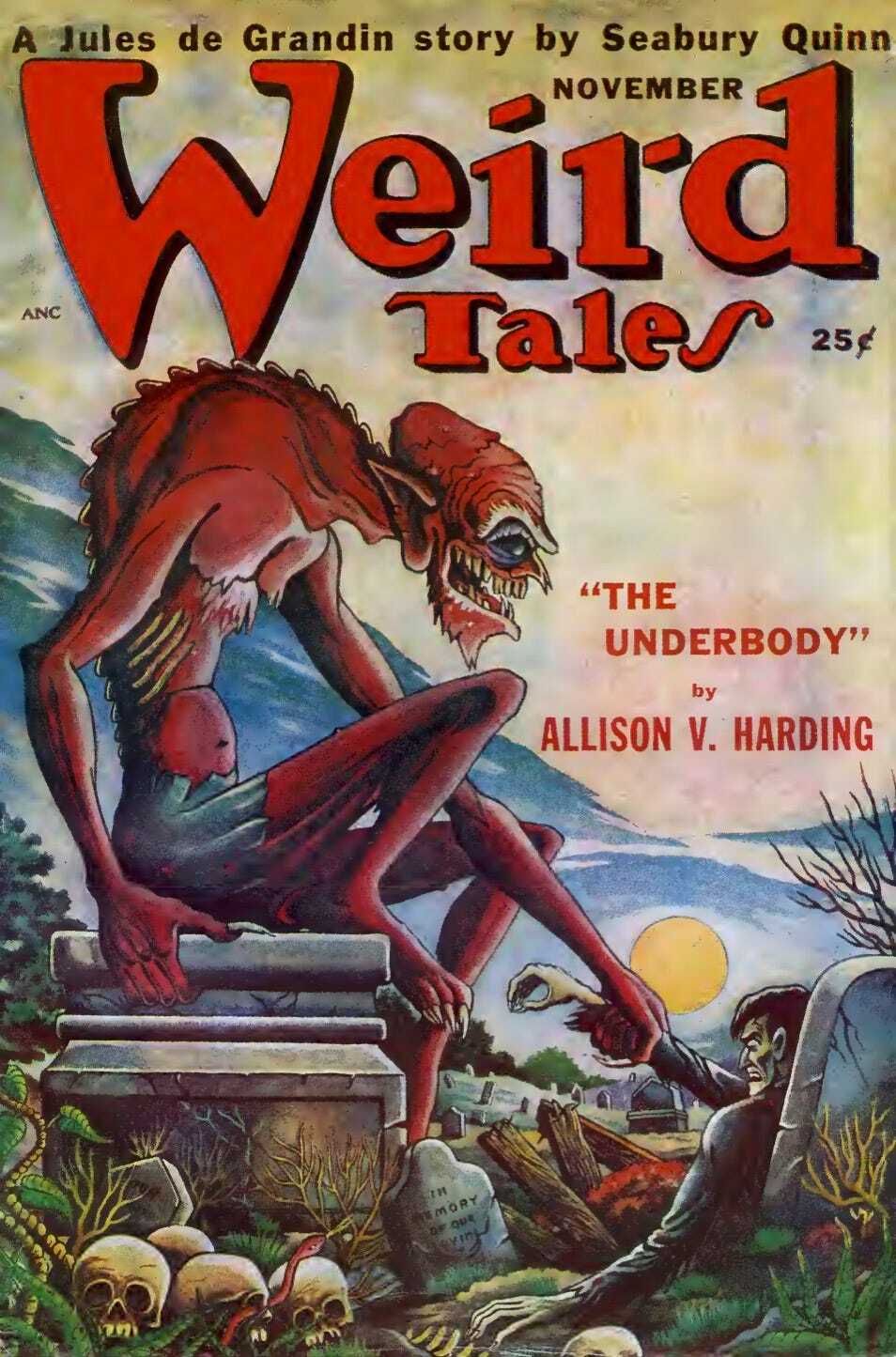

- The Underbody by Allison V. Harding

The Underbody by Allison V. Harding

The country fields of summer hid, within their rich earth, a terror-rid doom to transcend men's ability to fear.

There was a soft summer rain which meant “Stay inside,” but with Mother away visiting, Jamie had run out the back door—Father was in the library reading and Cook was in the kitchen baking—across the lawn and down the path that ran into the meadow.

Dr. Holland sat in his favorite leather easy chair in the library, half reading but more interested in looking out the window. It was warm enough to be in shirt sleeves; he was glad that there seemed to be no patients who would need his attention that afternoon, for like the sparrows outside he felt a reluctance to move in the heat and humidity.

There was no sound except the soft hiss of the rain as it touched the griddle-hot earth still overheated from the morning’s blazing sun. No other sound except the occasional happy noise of Amanda in the kitchen whipping up cake batter. Amanda was one of those country prizes found in small towns. She filled in when needed and did just what had to be done, as on this occasion, for instance, when Albert Holland’s wife had gone across the state for a two-week visit with her own folks.

It was nice to sit here like this not doing anything—the medical journal in his hand had an interesting article, but he didn’t have to read it this afternoon. He wondered idly what kind of cake Amanda was whipping up, he hoped it would be one of those thick white ones with chocolate icing and jelly fill.

And it was just then that he heard Jamie yipping and hollering, the sound of his small-boy voice coming from outside, getting louder as the little legs drove him closer.

Jamie had a secret. It was the biggest secret he’d ever had. Too big for its excitement to be contained in his small body dressed garishly in last Christmas’ cowboy suit. After looking and looking to be sure, he ran away from it through the field and up the meadow hill, over the stone wall and across the lawn, his little feet splattering through puddles. He started to call before he reached the house, and his father met him at the back door.

“Young man, come in here directly and wipe your feet!”

“Daddy!” gasped Jamie, all out of breath.

His father marched into the library. “You know perfectly well, Jamie, you wouldn’t have been out playing cowboy and Indian in this rain if your mother hadn’t just gone away!”

“Daddy—“

“Young man, it won’t look good for either of us if when Mother gets back, you’re sniffling around with a head cold. I think you’d better go upstairs and change. Let me feel those shoes and socks.”

“But, Daddy! Daddy… !”

“Yup, they’re wet! Now march yourself upstairs.”

“But there’s a man out there in the field, Daddy, lying all in the ground looking up at me!”

“Now don’t you try and get me in on your Indian games, Jamie.”

“Really, Daddy, hones’ and truly—come an’ see!” The little boy’s voice rose to a crescendo and he pulled at his father’s hand.

“You take yourself upstairs, young man, and change out of that costume. If you want to put on rubbers and a slicker, I’ll walk out there with you. What did you say this was … an Indian chief?”

“It’s no Indian chief, Daddy. Just a man lying there in a hole in the ground!”

“If you want me to go outside with you and help you hunt Buffalo Bill, you go upstairs and do as I told you!”

The little boy clattered away. A few moments later, father and son walked across the lawn over the stone fence and into the fields beyond. The drizzle was over, but mist had taken its place and clung with gray fingers to the meadow.

“Don’t tug so, Jamie. Anyway we want to sneak up kind of careful like! I don’t want an arrow through me, partner!”

Jamie’s excitement increased as they reached the far side of the meadow. There between a boulder and a tree stump he stopped, he looked at the ground and then he looked up at his father crestfallen.

“Mister Mole was there, Daddy, right there!” He pointed.

There was some newly turned earth here, the top of it muddy from the rain, as though Jamie himself or someone else had used a spade. Dr. Holland poked at it with the tip of his boot. There was nothing.

“Guess the Injuns got to him before we could, Jamie. Or maybe a mountain lion got him!”

“He was right there, Daddy!”

The physician laughed and put an arm around his son.

“Back to the house with you, youngster.”

He liked the boy being imaginative. To him it signaled brains, and that in one’s progeny never displeases a parent.

That evening at supper Jamie seemed unusually quiet, and Dr. Holland wondered if he’d made enough of the episode. To please his son he brought it up again.

“Why did you call that varmint Mister Mole, Jamie?”

“Because he was in the ground—stuck in the ground kind of, Daddy.”

In the mornings the physician contrived to get their breakfast.

“I’m not much of a cook, Helen” he had confided to his wife, but she laughed and said, “Well, you men can’t starve with Amanda getting two meals!”

Later this particular morning the schedule called for him to pick up Cook and she would spin her magic in the kitchen.

Dr. Holland was having a poor time with the breakfast dishes when Jamie came tearing into the kitchen.

“It’s Mister Mole agin!” In one great gush of air.

“Jamie … now look, you’ve tracked dirt in here. I don’t mind, but you know your mother’s told you not to do that and it means Amanda will have to clear it up. Maybe we’d better.”

“Quick, Daddy!” The little boy was already pulling at Dr. Holland’s apron.

“Quick, before Mister Mole goes away!”

The Doctor went, something less than willingly, but forced along by his little son’s urgency, out the back door again and across the lawn. And much nearer the house this time, just over the stone wall was a hole—funny, he’d not noticed that before; his son was getting to be quite the boy with the shovel—and in it. . . . Dr. Holland stopped so abruptly that his hand in Jamie’s pulled the little boy off balance backward.

“See, Daddy! See, it’s Mister Mole, like I told you!”

There were two steps to be taken to the hole in the ground and Dr. Holland took them, instinctively pushing his son back a bit as he did.

The thing in the hole was . . . a man . . . or had been! He was dressed in nondescript brown jacket, shirt and trousers, shoes, and his skin had something of the color of earth too, and there was earth coming from his nostrils and his ears and at the corner of his mouth.

His eyes were opened staring upward—for he was lying on his back—as Holland knelt beside the thing, her noticed the quirk of the lips. The man, whoever he was, could not have been very pretty in life, and the leer turned the face into a distasteful grimace.

The Doctor reached for the wrist. As he lifted it to feel at the pulse, earth fell away from between the fingers. It was as he expected—no beat. He slipped a hand in under the man’s jacket and felt over the heart region. There was not the slightest vibration.

He rose, and herding his son before him, hurried back to the house.

“You see, Daddy, I told you about Mister Mole! He comes out of the earth!”

“Now, son, I’ve got some things to do and I want you to stay here.”

So there had been someone yesterday! Jamie must have become confused and led his father in the wrong direction.

Holland was due soon for a call on Mrs. Foster, whose nagging arthritis and irritable temperament demanded punctilious attendance by her physician. He thought calling Ed Quinlan the next house away. Quinlan, aside from being town clerk, was also deputy sheriff of the district; but instead, professional curiosity made Holland first reach for his small medical bag and head out again to that grave across the lawn, unraveling his stethoscope as he went.

He was quite sure . . . well, positively sure, that the man was dead. The shock of the whole thing—his son, of course, didn’t realize the dreadful significance of this gruesome business. He walked briskly—he figured afterward he could not been in the house more than five minutes, and yet . . . yet when he returned and stood there where the spot was, the thing, Mr. Mole, was gone!

“Impossible!” Holland murmured half to himself.

This was the place, no mistake about that. The loose earth; he sifted it with his fingers. There was nothing! Nothing! He stood from kneeling and looked around, half fearful that he would find this man he had thought—no, he was sure—was dead walking somewhere away from his earthy grave. There was no one, and he could see a good ways in every direction!

He folded his stethoscope thoughtfully and returned to the house. It came to him that this might be some sort of outrageous joke played by persons unknown, like the time some of the high-schoolers had monkeyed with the pipe on his birdbath and a fire-hose stream of water had come out instead of the usual graceful spray the birds welcomed.

But still it had been a body and it had been dead. That would mean either grave-robbing or a corpse from some morgue or hospital laboratory.

He instructed Jamie to stay indoors “positively, and don’t you dare disobey me” until he got back.

He made his call to Mrs. Foster as short as possible, picked up Amanda and drove back at a great rate to find his son unconcernedly plaything with his toy soldiers on the library floor.

Once, twice during the day the Doctor walked out to the plot of loose earth beyond the wall. Once he went out into the fields where Jamie had taken him the previous day. There was nothing to be seen except what looked like an area of spaded earth.

No more was said until that evening when Jamie brought the subject up just before being ordered to bed.

“Where does Mr. Mole go, Daddy?”

That was a stickler! If you presumed Mr. Mole existed, he couldn’t just vanish without reason and to places unknown. If you presumed Mr. Mole didn’t exist, then Dr. Holland should instantly fetch his son to an eye doctor and get himself to a psychiatrist!

For several days Dr. Holland thought a lot as he went about his doctor’s tasks and as he puttered around the house being a father, and he found more than a few excuses to walk around the lawn and across the stone fence into the meadows beyond.

In a few days the holes where Mr. Mole had appeared lost their freshness, lost their appearance of having been newly turned and again were claimed by the broad bosom of the earth.

It was one evening just before bedtime that Jamie said, “Mister Mole invited me to go for a walk today, Daddy!”

Holland almost dropped his pipe cleaner. He tried to keep his voice steady, for in the silence that had surrounded this subject for several days, it was as though that ugly dream had been swallowed up. The physician kept his voice even with an effort.

“Where was he, Jamie? Where was Mister Mole?”

The little boy indicated with a vague sweep of his arm and repeated again, “He asked me to take a walk with him. Down below, he said, Daddy.”

“Jamie!” This thing had gone far enough. “I want you to tell me, when did you first see Mister Mole?”

“The time I told you. That rainy day.”

“And, Jamie . . . hones’ Injun, now . . . he talks to you!”

“Sure, Daddy”

Holland rose to his feet. Something now would have to be done. This could be set upon or dismissed with the hopeful conclusion that it was, after all, only a figment of the imagination.

“Let’s go see Mister Mole, son, right now.”

“But you can’t! He’s gone! He went right while I looked!”

“Which way? We’ll follow him.”

The boy crinkled up his brow as though even to his young and credulous mind, the event was unusual.

“He just kind of went. Down into the earth like. He said he’d be back.”

The physician got his son to tell him the whereabouts of Mr. Mole’s latest appearance and then bustled the six-year-old off to bed. He looked for himself later, and there about where his son had described it were the markings of freshly troubled and tossed earth. Precisely what to do was perplexing. His ordered scientific mind made Dr. Holland seek some definite, logical action, and yet there was none.

The thing—whatever it was, and it appeared to be a man—should be examined by the authorities. The first step in that program though, was to find Mr. Mole and constrain him from any more of his vanishings.

Albert Holland spent twenty-four hours thinking over a course of action and then the thought came to him that he should talk to his neighbor, Ed Quinlan, the deputy sheriff who lived across the long meadow that ran out back and down the hill apiece. Quinlan, a widower with a son about Jamie’s age, was a nice fellow. He’d always appreciated that Holland had treated him without mention of a bill when things had been tough for the Quinlan’s a while back. And he showed his appreciation. But more, he was a bluff, realistic individual whose long suit was not imagination—though he was not stupid by any means—and would, therefore, bring a good slant to bear on this proposition, plus the weight of his official office in the county.

Holland was going to stroll over there this very evening, and now with Jamie bedded down, he was about to start when the knocker of his own front door sounded. It was, coincidentally, Quinlan.

“Hello, Ed!” The physician greeted warmly.

“Evenin’, Doc. Sorry to bother you.”

“Not at all. Come on in.”

Holland saw immediately that the man was agitated. His broad, ruddy face looked worried and his big thick-fingered hands gripped at the somewhat worn Panama he was never without.

“Missus still away, Doc?”

“Yup, another week, Ed.”

They talked of things like this and that for some moments and then Ed got around to the point.

“Doc, if your youngster’s safe in bed, I wonder if you could walk down toward my place apiece. Something funny has happened.”

Holland waited, his own feeling of uncomfortableness increasing.

“My son, Eddie, Doc. Damndest thing you ever know. He came across a body lying out there—in the meadow back of our place. I thought the youngster was pulling my leg . . . you know the way these kids carry on. Kept after me all afternoon, he did. I went out with him just now, Doc. Seen him for myself, I did. All stained from the earth, kind of grinning like. Was the spookiest lookin’ fellow you ever saw, Doc. I felt of him myself. Didn’t have no more warmth anymore than a tree. Sure he looked dead, although I can’t really say if there’s been some crime committed.”

Quinlan stopped and took a deep breath, fiddled with his hat and then fixed his troubled eyes on the doctor again.

“Would you come along with me?”

“Why sure, Ed.”

Quinlan hurried on: “I think I saw the fellow move. It was getting kind of twilight out there. I’d sent Eddie back to the house for a flashlight. To be honest, I couldn’t see so good. But, Doc, he’d been lying on his back with the earth and all coming out of his mouth like, and when I looked again, I could swear he’d kind of rolled over. But there was still this grin on his face like he’d died smiling—only it wasn’t a nice smile—or if he wasn’t all dead, he was enjoying this.”

The man rattled on, following the physician out into the hall as Holland went to the coat closet to get his own flashlight.

“I’ll go with you, Ed.”

“But here’s the thing, Doc.” Ed’s hadn’t held him just inside the front door as they were about to step out into the darkness of the summer evening. “I lost him. I must’ve been watching through the gloom for Eddie to come back with the light and all, but I turned around and he was gone—just like that as though he’d Neve been there ‘cept that I knew he had ‘cause the earth was all turned up new-grave like!”

The two walked then, the bobbing flashlight held in Holland’s hand showing the way across the lush July countryside. The night with them and silence now between them; this lawman and the man of science , each with his thoughts and his puzzlement until they stood together, close together, brought there by Quinlan’s sense of direction and the bobbing shaft of light that followed to its goal.

Ed’s voice sounded small under the black archway of night as he breathed out and said, “There’s where he was. Right there, Doc.”

And Albert Holland stood and looked at the ground, the familiar look to it. Stood with flashlight beam steady, for there was nothing to do. They both were thinking what to do next and there was no need to say it. Finally Quinlan spoke.

“Guess you think I’m crazy, Doc.”

And at that, the physician put his hand on the other’s arm.

“No I don’t, Ed. You’re not crazy. You saw something.” And he was going to say, I saw it too, Ed. Out here in the meadow and then back nearer my house. Jamie called me just as Eddie called you. We’ve seen something all right—in God’s heaven just what, I don’t know and I’m a doctor and supposed to know what life and death look like.

But he didn’t say it because Quinlan was talking some more:

“. . . claims he talked to him—imagine this, Doc, a corpse speaking to him—and invited Eddie to take a walk with him, although he couldn’t be a corpse moving over onto his side, could he? People can’t do things like that—if they’re really dead, Doc, can they?” The deputy sheriff was plaintive.

Holland put his arm on the other’s shoulder again, this time with more urgency.

“Ed, you say you shooed Eddie home before you came to my place?”

“Why, sure . . . sure!”

Then the two almost automatically started walking towards Quinlan’s small cottage just over the brow of the hill, and as they walked, though nothing more was said, their steps speeded.

It was the night that did it, Holland told himself, the night that puts fear into even the most unsuperstitious man, the most prosaic, the most unimaginative, but by rights they should feel that way, for this experience the two fathers shared with their two small sons was—poor weak word—extraordinary!

There was a light on the ground floor of the Quinlan house and they could see it through the gloom and it grew bigger as they walked hurriedly towards it. Quinlan, a tightness in his voice now, called as they went forward.

“Eddie! Eddie, lad? Are you there? It’s your dad!”

And from the bigger bulk of house ahead of them through the night the small boy’s voice came back.

“gee, Pop, is that you? You been out there in the meadow talkin’ to him?”

There was no need to answer. Almost simultaneously, their hurrying steps slowed. The crisis, not declared between the two men but appreciated by both of them, was over. Quinlan turned to face the physician.

“Thanks, Doc. Thanks a lot for coming over.”

In the dark the two men shook hands. Fervently, it seemed. And then they parted to go their separate ways in the darkness—Quinlan to his home and Dr. Holland back across the night-grown meadow.

Holland sat up till very late that night thinking of the chain of events which were now more than the imaginings of one person or two. Quinlan was his antithesis, his opposite and antidote, and yet the plain, good-hearted man had seen. The possibility of this being some ill-mannered joke was quite implausible. Aside from any other objections, people don’t play that kind of joke on a deputy sheriff, even if the town physician is less immune. No, there was something out there . . . somebody. He was a man, or had been once, for he looked it and he wore clothes.

There were, Holland was well aware, cases of improper diagnosis. Persons have been declared dead who were not dead. There are diseases and conditions and states which resemble death and yet are not. The catatonic is one, for instance, and yet beneath his reasoning, beyond his speculating and his attempts to lay out at least in his own mind each possibility, and then rationally to plug these loopholes, he was certain as a physician that the man he had seen, the one Jamie had—so aptly wasn’t it—called Mr. Mole, was not of the living.

He wished Helen were here for she was not only a good listener—and he needed such to parade his facts and suppositions before—but she had good suggestions. The night insects were quiet and there was a hint of light in the east when the physician retired to his room.

To explain to Jamie that he was not supposed to run small-boxlike far and wide across the meadows necessitated the thinking up of a story about Indians on the move outside.

The little boy looked at his father closely, more wisely, the physician thought, than a child of his years should.

Holland went about his business glad that the days were six, five, four, then three until wife Helen would return. He could not in all conscience restrict his son to the house for there had to be a reason more than make-believe Indians and the danger to the small, tow-headed boy was not proven, dwelling perhaps more in a father’s mind than anywhere else.

As the days passed, the physician chided himself a bit. He became annoyed at the feeling of uncomfortableness that he experienced when he needs be, got the coupe with the physicians’ emblem over the back license plate, out of the garage to go on some necessary call or errand, and yet still felt uneasiness at leaving Jamie.

But the very passing of time gave strength to the hope that grew almost to conviction that whoever it was, whatever it was out there in the ground, moving like a mole from place to place, had gone back to whatever place from whence it had come, or had been stilled forever in some dark crave e beneath the earth’s surface away from men’s eyes.

Holland met Quinlan one day down in the village, and both men’s spirits were good.

They didn’t say so, but the meaning was clear. I haven’t seen him nor have you or we would have spoken of it. The knowledge was between the two men and then they parted cheerfully.

The night before the good day Helen was to return, Holland’s phone rang. Jamie was already upstairs, presumably asleep in his cheerful, wallpapered east room, and Holland had long since given Amanda a lift home explaining to her carefully that they’d “want her later on the morrow” because Helen would be coming back in time for supper and it would be nice to have something extra-special for her homecoming.

“Hello, Doc,” it was Quinlan when Holland picked up the receiver. “Eddie’s seen him again!”

The doctor’s hand tightened on the instrument.

“Out back in the woods a piece. Swears he moves around an’ talks to him. Wanted Eddie to take a walk with him.”

Holland tried to keep his voice even: “What’s to do about it, Ed?”

“Tomorrow . . .” Quinlan added just as though he’d thought it out, “. . . I’ll get a bunch of us together and we’ll find out who or what this is! Maybe it’s some kind of queer drunk.” This last, hopefully.

“I think we out to do something, Ed,” the physician said resolutely. “Can’t let this go on, you know!”

On that note the two men hung up, Holland to re-enter the library where he sat, the uneasiness with him again. In the last few days he had found the time and opportunity to peruse both the county clerk’s and newspaper records. There had been no unaccounted-for disappearances or other incidents in this area which would explain this peripatetic “thing” which haunted the summer countryside. And in present-day society the hardest thing in the world to do is to disappear or get oneself killed or destroyed in any way without attracting considerable attention.

Yes, whoever heard of an unclaimed body or corpse? Try as he would, Holland could not dissuade himself from the nagging thought that here was something that did not fit in with the commonplace and, therefore, did not follow everyday laws of the workaday world.

Actually, it was a few minutes past seven the next morning when Holland heard his front-door knocker clattering. It seemed much earlier. The rain and mist across the land had held up the day. Jamie was just stirring in his room as his father clumped down the stairs muttering under his breath.

And then before he put his hand on the great knob that would turn the door to open it, a feeling of presentiment took hold of him, stiffened his arm and touched his back with damp, cold fingers.

He pulled the portal open, and out of the early morning grayness stepped Quinlan, in his arms a bundle, his but face wide-eyed, storm-streaked. He seemed to offer the thing cradled in his arms to Holland and Holland, seeing, suddenly became the physician.

He said gently, “Here, Ed. Let me take him,” though he knew at first look it was no good.

There was dirt all over little Eddie; dirt turned to mud by the rain in his eyes and mouth and ears. The youngster had died, it was apparent, of suffocation—not from hands wrapped around his throat, but from going down deep, deep into the earth and being buried there.

The thought came back to Holland of what Quinlan had said over the phone the previous night, what his own son had said the last time the “thing” had visited over here—what was it?—Mr. Mole had invited him to take a walk below?

As the physician was thinking, Quinlan was talking brokenly, trying to hold onto himself with the will of a strong man, twisted and bending under the cruelest tragedy of his life.

“I’m sure the youngster was to bed when I talked to you last night, Doc, but sometime in the night or early this morning, he must have gone out—God knows why—‘cept that that devil has a power, a kind of fascination! I’m up early, you know, and Eddie was nowhere around the house this morning. I went out to look . . . and there was one of those holes not far from the house. You know . . . like we’d seen before. Seen little Eddie’s footprints, I did, around this place like they went into the hole. . . .

“. . . I got me a spade then, Doc, and I dug faster than a man’s ever dug before . . . and after I got down a ways in that hole . . . I found him . . . like this. But there weren’t a ‘hello, Daddy’ or a breath left in ‘im at all. . . .”

Quinlan sank down on a chair, sobbing now, his head between his great, strong hands, shaking like a terrified child.

“Ed,” said Holland quietly, and sympathetically. “Ed, follow me into the medical room.”

The physician led the way, carrying Eddie’s body in his arms, and Quinlan dutifully lurched along behind. Jamie was a sensitive boy. Holland could find no use for having him look down the stairs through the bannisters and see the scene in the front hall. Also, Quinlan himself needed some medication.

The doctor laid Eddie’s body carefully on the examining table, made sure with his stethoscope what he already knew—that there was not the slightest flicker of life left in the earth-choked body, and then mixed the unfortunate boy’s father a potent sedative.

“He’s gone, isn’t he, Doc?”

“I’m afraid he is, Ed. It’s a terrible thing . . . terrible! And I know any words of sympathy now from me seem poor and inadequate.”

Quinlan sat for a time, not saying anything, turning the glass that contained the sedative around and around in his strong fingers. He drained the medicine, and after a while, stood up.

“Well . . . thanks, Doc. I’ll take my son, if you please. Take him home and then down to the undertaker’s. I want to go quick, Doc . . . ’cause I’m going to get after the devil out there in the ground! I’m going to get the men together. You’ll join us, Doc?”

“You know I will, Ed. I’ll come over to your place a little later in the morning.”

“You got an axe, Doc? Bring it!” The deputy’s teeth bared in a snarl. “We’re gonna get this fellow!”

“Ed . . . don’t you want me to go with you, or take little Eddie down to town myself?”

Quinlan shook his head determinedly, “What’s done’s done, Doc. Now we gotta get after the one who did this!”

He went out with Eddie again cradled in his arms, and the growing morning, as the light of it touched his face, showed it set in hard lines, the terrible sadness, shock and despair replaced with something else that was healthier in man.

Holland went for Jamie then and was steeled when the boy asked, “Daddy, what was Mister Quinlan doing here?”

“He had a very great problem, son,” the physician replied carefully. “He came to ask me about it. How about driving into town with me, Jamie, to pick up Amanda?”

As they drove, the cloud scurried away before them and the sun came out to dry and heat up the wet, early morning world. Holland drove numbly and instinctively. He returned Amanda’s greetings automatically. There was nothing to be said, but already, his son was looking at him curiously.

That was one of the curses of imagination. Amanda was old, good to bake cakes and make apple pie dumplings and filled with the desire to serve them and affection for them as a family, but she was too old to understand if he said, “Now look Amanda. Something terrible has happened in this neighborhood. There’s a man loose . . . a dead man, and he’s just killed a little boy. We have to be careful . . . we don’t know from what direction danger may come. Maybe it won’t come but there’s the situation!”

He couldn’t talk like that to her, or even if he could, not in front of his son.

They arrived back at the Holland house, and Amanda noticed at once that the physician had not gotten any breakfast. She insisted on getting something together. Holland ate poorly. Afterward, he must get over to Quinlan’s as he had promised. The men would be gathering there for their grim task.

Jamie, from behind his glass of milk, said to his father behind his coffee cup, “I’m going over to play with Eddie this morning. We’re going to fly the new kite, Daddy!”

Albert Holland swallowed with difficulty.

“No, Jamie, not this morning.”

“But, Daddy—!”

What could he say? Whaat could he say? Not “Jamie, I have something to tell you . . . Amanda’s too old and you’re really too young to understand the why of this, but the facts are, Eddie is . . . dead! He was pulled into a hole by a corpse and suffocated out there in the meadow where you and he have played so many times . . . where you were going to play this morning with your kite. He’s dead, Jamie. No use looking for him out there.”

How could he say that? What could he say? And all the time Jamie sitting there, tow-headed and wondering why.

“Daddy, we’re going to . . .”

The boy’s quick mind kept searching around his father’s silence.

“Is he sick?”

(That’s a doctor’s son for you.)

“That’s what it is!” Said the little boy, gathering momentum and sureness. “He’s got measles!”

No, Jamie, that happened last winter and you don’t get them twice, but you still remember how Helen and I wouldn’t let you go over because Eddie had measles. This time, Jamie, it’s something worse . . . oh, so much worse than measles.

“It’s something catching, Daddy? Measles?”

“No.”

No, Jamie not measles, not something catching—not really. Or maybe it is! Maybe that’s why I’m more frightened than I’d ever dare let you know. That’s why in a moment I’m going to get the axe out of the woodshed and go over and join Quinlan and the rest of the men.

Instead he said, “No, Jamie, you can’t go over this morning. Find something to do around here. And don’t you disobey me! I’m going to tell Amanda to keep her eye on you, hear?”

Albert Holland walked towards Quinlan’s, the axe in one hand, across the low stone wall into the meadow and towards the hillside. The sun was out now, accentuating the softness and the peace of mid-summer. The fertile greenness soothed his eyes and made the unpleasant thoughts in the physician’s mind seem incredible and implausible. That these things could have happened under the blueness of the sky, the brightness of the sun here in the softness of the land was surely not possible.

And yet as he walked further, he saw the knots of men standing around Quinlan’s house. From a distance they were short men and tall men, fat and lean. Here and there the sun touched a gun barrel. He recognized faces as he came closer—a drugstore clerk, several boys from the volunteer fire department, the assistant postmaster, others. They nodded to him and he nodded back. And there was one thing they all had in common, and that one thing was grim and unsmiling.

Men made suggestions and barked orders at one another, and finally they walked out onto the broad bosom of the meadow taking their shovels and axes and clubs and guns with them, prodding at the earth, poking at it as though it, itself, had committed this awful crime.

Quinlan was everywhere, filled with a terrible rage that was the worse because it was silent except as it came out in the man’s unquenchable energy.

The hours passed, and the men plodded across the fields, sloshed through brooks and tramped through underbrush. They had long since poked and spaded into the holes Quinlan and Dr. Holland knew of. Midday passed and afternoon. The sun slid towards the rim of the westerly hills, and Holland, consulting his watch, knew he should be getting back to get things ready for Helen.

With the fatigue of walking, searching, there came a feeling of futility. What had they done . . . what could they do? What did the know, tapping their boots and steel instruments against the ground here and there for something that would not stand up fairly and say “Here I am!”

In relays some of the men came back to Quinlan’s cottage where womenfolk were keeping coffee pots on the stove. Holland left his axe at Quinlan’s and turned his steps towards home. He told himself that sooner or later they’d have to uncover this creature—whatever he was or it was. It was good, he thought with a physician’s analysis, that Quinlan had the direction of this posse on his hands at this moment of his so-great sorrow.

He made the house, went inside, the screen door slamming behind him. The noise of Amanda in the kitchen drew him there. She was “making something special” for the supper when Helen would be with them again.

“Where’s Jamie?” He asked loudly.

Amanda was a little on the deaf side and had to be bellowed at.

“He’s around—playing in his cowboy costume, he is.” She waved an old arm in a semi-circle. “Doctor Albert—“ she always called him that—“Doctor Albert, you look a fright! Whatever have you been doing?”

Holland looked down at himself. Five or six hours of walking through thickets and looking at dirt holes in the fields had left him rather bedraggled. He’d have to clean up. The physician looked out the window.

“Where did you say Jamie was?”

“Round somewhere,” she repeated again. “Saw him not very long ago. Well, now maybe it was an hour. Had a friend, he did. Mister Somebody-or-other come to see him.”

Holland froze. “Mister . . . Mister Mole?” His voice was much louder than necessary.

“That’s it! Knew it sounded like an animal. Peculiar handle, isn’t it, Doctor Albert? Said his friend invited him—this Mister Mole—to take a walk down below. Must mean towards the meadow, Doctor Albert.”

But Holland was gone, flinging himself out the door, running and trying to look in all directions, the inner hand clamped over his heart tightening, agonizing. . .

The house was behind and the lawn and the stone wall, and then in the woods in the other direction from the meadow, he found it. A new hole like all those others!

Holland went at it with his boots and hands, wishing he had something else, but there was no time to run back for a tool. He scooped and kicked the earth away as fast as he could. And by and by a corner of material showed and then he had it in his earth-coated shaking hands. It was a hat—a small boy’s cowboy hat . . . from Jamie’s outfit!

The doctor redoubled his efforts then frantically, clawing, getting down on all fours, and finally he found what he knew was there, and shaking away the earth covering and clinging, he laid it on the rim of the hole he had excavated with his hands . . . the same size bundle as Quinlan had brought to him the night before, equally lifeless and useless now.

Holland made a noise like an animal, and like that animal, he dug on, hollowing and scooping, for it was for him to do this thing. He would have to stop it. The old who had forgotten how to dream and who don’t want to believe, like Amanda, and the very young who still believe in everything, like Jamie—they had caused this, unknowing.

He ent on and on, a man in an earthen hole in the green countryside. And it must have been hours later that Amanda, wondering, came looking and heard the noises from that place in the woods. She got men from the posse over at Quinlan’s, and they found him like that in an unbelievably deep hole of his own making, with the small earth-caked body of his son lying guard above. It was Quinlan himself, who pulled Albert Holland out, and later with Helen, who had arrived home again, tried to reassure and quiet the physician. Helen, whose shock, at finding this terrible tragedy in her own family, was only slightly more than the frightening condition of her husband.

For Dr. Holland was not a man of science any more, nor a physician but a squealing, screaming, crying creature, stuffed with earth that came out of him when he talked. They sent for another doctor up at the county seat to come quickly, but there were miles in between, and meanwhile Holland had the time to tell over and over again how they shouldn’t have pulled him out of the hole in the earth, for twice, three times, more, he had caught up with Mr. Mole down there. He had felt a trousered leg, an arm, a torso, and it had wriggled and twisted away from him like a worm in the earth.

Yes—and it had leered at him!

“It speaks and it moves!” Holland ranted this over and over.

Sometimes in his horror he screamed so loudly that he frightened the birds outside in the twilight of the July evening, and even poor, old half-deaf Amanda far away in other parts of the house staying, with her kindly tear-streaked face, because “Maybe there’s something I can do,” would clap her withered hands to her ears to keep the awful sounds from them.

But Albert Holland’s screams did not carry far enough, for later, not too much later, across the green land cooling in evening, a blond child named Janice ran across the spongy green ground—a child who believed in fairy stories, in everything—running and calling through the evening, filled to bursting with the secret as she ran.

“Mommy! Daddy! Guess what! Guess what I’ve found!”

Allison V. Harding published stories in Weird Tales from 1943 to 1951 and is perhaps most well known for a series of stories featuring the loathsome stalker, the “Damp Man”. Allison V. Harding is also a pseudonym but as to who is actually responsible for the stories under the Harding name is something of an open question. The general belief appears to be that the stories come from Lamont Buchanan and/or Jean Mulligan. The artist and writer Terrence E. Hanely has written about Harding since 2011 and has detailed his own efforts to determine the “true” author of these stories. I would recommend reading Hanely’s blogs on the subject with the advance warning that the October 4, 2022 piece titled “Takings and Turnings” is just a bunch of transphobic garbage that has little to do with Harding and may sour your opinions on Hanely’s other work as it did mine.

Reply